Heracles who was the son of Zeus and Alkmene was born in Thebes but as an Achaian he was cousin to King Eurystheus of Tiryns, the instigator of his famous labours. He is perhaps the most popular of all mythological heroes and many are the tales told of him and much truth lies concealed in them. The myth of Heracles notes his close relationship with Marathon and tells how his children sought asylum with the King of Marathon. It is therefore of some interest to learn that archaeologists have found in Marathona well-hidden tomb of Mycenaean date.

The myth of the wild bull which wrought havoc throughout the land was well-known in Marathon. This bull, killed by King Theseus of Athens, dates from the threshold of history and may represent the uncontrollable waters which, until means were found to channel them for irrigation, caused incalculable harm. When Theseus lived is unknown but he was responsible for the first known political reform in Attica when all its inhabitants, Eleusinians, Acharnians, Marathonians and the rest became Athenian citizens without renouncing their local privileges. He thus lay the foundations upon which the reforms of Draco, of Solon and of Cleisthenes were in due course based.

It was Cleisthenes who abolished the old clans and created ten new ones which comprised all the inhabitants of Attica without discrimination in respect of wealth or status. Each of those clans elected fifty deputies and these collectively constituted the source of all power in the state. Two remarkable laws characterized the new regime. One was the law of ostracism which made legal the exile of an Athenian upon the request of his fellow citizens confirmed by the com-munity, even if he was innocent of any crime. Its purpose was to rid the city of potential tyrants. The second law introduced the democratic procedure of electing officials and rulers by ballot.

When, therefore, clouds began to gather on the Attic horizon Athenians were reaping the first fruits of their new-born democracy and their morale was high. That is why in 496 B. C. they responded so eagerly to the plea for help which came from the lonians of Asia Minor who were in revolt against Darius. But the sack of Sardes by the allied forces of Ionians, Athenians and Eretrians gave the Persians a pretext for the idea they had long entertained of invading Greece.

At the first attempt to implement this policy Mardonius, the leader of the expedition, was drowned near Athos. It was a second expedition, led by Dates and Artaphernes and the Greek tyrant Hippies Pisistratos, which ended at Marathon when Athens acquired great glory.

Though communications at this period were not highly developed the Athenians were cognizant of Persian intentions and fully aware of the danger in which they stood. Hippias had his supporters within Athens but there were fewer Athenians than Eretrians prepared to betray the city in which they had a stake. When, therefore, the news came to Athens that the Persians had destroyed Eretria, the people were prepared to play their part.

It was fortunate for the Athenians that Miltiades, a powerful character, who had played an important part in the governance of the Thracian colonies of Athens, knew the Persians well and looked beyond the narrow confines of Attica. He suggested the destruction of the bridges built by the Persians across the Danube but having failed to persuade the colonists of this necessity he returned to Athens. There not only did he encourage the people to resist the enemy from Asia but he convinced them that to give battle was their only effective means of doing so.

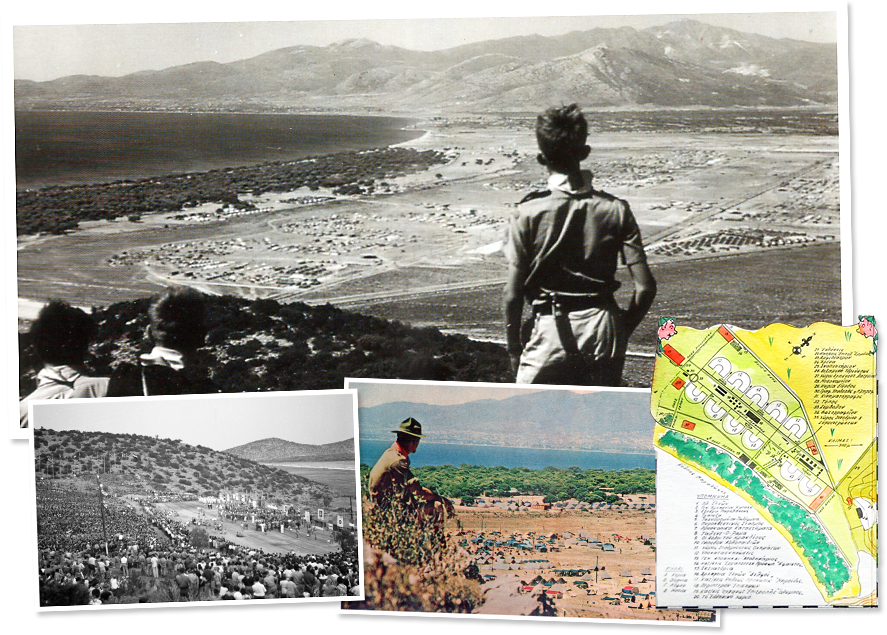

The plain of Marathon to-day differs little from that of two thousand five hundred years ago. The same mountains overlook it and waves of the same sea beat upon its crescent shores.

Though the larger marsh which bounds it on the north and the lesser marsh which bounds it on the south have been much reduced, they have not disappeared. The area is still approached from Athens by two roads. The longer but easier road skirts the sea and enters from the south; the shorter but more difficult road crosses the mountains to debouch into the plain on either side of Mount Kotroni.

Of the ancient towns little remains. The site of Marathon is marked by some shepherd huts at a place on the mountain road called Vrana; but its name has been transferred to a modern village on the site of Oinoe. Provalinthos has given place to the modern Nea Makri; vestiges of Tricorythos’ have been recognized in the hamlet of Kato Souli. Agriliki where was once the Sanctuary of Heracles, is in the Valley of Avloni looking across to Mount Kotroni.

A visitor who takes the trouble to climb the hill and to view the plain from the Heracleion can easily visualize the remarkable scene when the army of Darius appeared with the intention of marching on Athens to chastise its citizens. In the bay, against the background of the Euboean mountains, was his mighty fleet comprising, besides the six hundred triremes bearing his infantry, many larger vessels carrying the cavalry horses which, because they had none, filled the Athenians with dread. Close by in the valley, hidden from the enemy by the bulk of Mount Kotroni. was the Athenian camp which served as Greek headquarters. Here the Athenians were joined by a contingent from Plataca, the only Greeks to come to their aid.

It is strange that the Athenians made no use of horses in the battle. Even the messenger sent to Sparta to ask for help, before the battle, and the messenger sent to Athens, to announce the victory, after the battle, were unmounted.

For ten days neither side made a move. This gave Miltiades, one of the ten generals leading the Greek army, time to assume the command and to ponder how best with an army of ten thousand freemen and as many slaves to combat the much more numerous enemy. On the tenth day Miltiades noticed a move for embarkation of the Persian army. This prompted him to expedite the clash. The Greeks took up a position on the plain in line of battle about a mile in length. This they achieved by reinforcing their wings at the expense of their centre. The centre was com-manded by Aristeides and Themistocles. The Persians responded by deploying to face them.

The Persians were renowned for their skill in archery and the Greeks for their skill in the use of their shields. Having offered the customary oaths in a loud voice the Athenians now advanced slowly but steadily towards the enemy taking care to keep out of range of the Persian arrows. Then they broke into a run and ran so fast that they were soon at close-quarters with the Persians (someone has taken the pains to calculate that the Persians could shoot 300.000 arrows against the Greeks -i.e. 15 arrows for each one of them- during the time preceding the fight at close-quarters).

But as a result of the speed of this attack which took the enemy by surprise and because of the good use they made of their shields the Greek casualties in this phase of the battle were small.

In what may be regarded as the second phase of the battle, the strengthened wings of the Greek army drove back the relatively weak Persian wings while the Greek centre fell back in good order before the strong Persian centre. When the well-disciplined Greek wings, on the order of Miltiades, now turned inwards and attacked the Persian centre from the rear, victory became certain. The Persians fled in a panic and many were trapped in the marshes. Flushed with victory the Greeks now hoped to capture the enemy fleet, but in this they were disappointed because very few ships had been drawn up on the shore. Seven vessels fell into their hands as did the Persian camp and they counted six thousand enemy dead. The Athenian dead numbered 192 but the number of Platacan and slave losses is not recorded. Among the casualties was Cynegiros, brother of the dramatist Aeschylos, who lost both hands when holding on to a Persian ship and even his head when he seized the prow with his teeth.

When the battle was over, Miltiades sent a messenger, Pheidippides, to Athens with news of the victory, who ran all the way. He had hardly whispered the words “We have won” (NENIKHKAMEN) and he fell dead, a glorious death which made him envied of all men.

The Athenians were unable to celebrate their victory as they would have wished for they had good reason to believe that the Persian fleet, which now set sail, was bound for Athens. Moreover Miltiades feared, that if his army relaxed the enemy might suddenly return and catch them in disarray. When, therefore, a mysterious signal was flashed on the summit of Pentelicus he rushed to Athens with the bulk of the army by the mountain route in a single day. Aristeidres was left at Marathon with two clans to care for the wounded, to bury the dead and to gather the booty. The Persians duly appeared in the Saronic Gulf but finding the army back in Athens they set sail for home.

The Athenians could at last breathe a sigh of relief. Great honours were bestowed on those who survived the battle and sacrifices were offered for those who had succumbed. They were buried on the field of battle and over their remains a tumulus was erected which may still be seen. But the ten columns erected in memory of the ten tribes, where for many generations the Athenians honoured the dead as heroes, are lost. Another tumulus covered the remains of the Platacans who received separate honours. Nor were the gods forgotten, for a tenth part of the spoils were allotted to them. The great statue of Athena which so long dominated the Athenian Acropolis and the Treasury of the Athenians at Delphi were now erected. Caves in the rock of the Acropolis and at Oinoe were dedicated to Pan, because the rout of the Persian army was attributed by the Greeks to their goat-footed god (it was now that “panic” was introduced into the Greek vocabulary, and from the Greek to other languages, with the meaning of unwarranted fear).

Seven hundred years later when the traveller Pausanias visited Marathon the memory of this decisive battle was still fresh in men’s mind and he records that lonely travellers crossing the plain would sometimes hear again the din of battle.

The honours bestowed on Miltiades and the authority rested in him exceeded what was permissible by law. He was made admiral of a fleet of seventy triremes and given command of an expeditionary force for a purpose known only to himself. Perhaps he planned to carry war into Persian territory or to punish those who had aided Darius. At Paros. where he had a personal account to settle, he failed in his purpose and was wounded. He was put on trial and only the fact that he was suffering from gangrene saved the victor of Marathon from prison and perhaps execution. His son, the famous general Cimon. inherited both his father’s glory and his debts. How are we to account for the attitude of the Athenians to their savior? Was it that they honoured him when he deserved honour and punished him when he deserved punishment?

Engraved on the monument erected at Marathon by the Athenians were these words of Simonides :

This epigram makes clear that the Athenians who fought at Marathon were fully aware that they had waged war not only for their city but also for Greece, for freedom and for democracy. If for "Greeks" we substitute "free peoples" the true importance of the Battle of Marathon for mankind becomes very clear.

An Athenian foot-soldier, named Phidippides, still wearing his heavy armour, ran the distance from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory against the Persians. It is said than no sooner had he reached the gates of the city and gasped "NENIKHKAMEN" (we have won!) that he fell down dead from exhaustion.

It was in honor of this interpid messenger that the Marathon Race was instituted at the first modern Olympic Games held in Athens in 1896, and has been included in the Olympic Games ever since.

On this same site, the Scouts of the World, gathered in August 1963 to strive for peace and a victory of high ideals.

The camp site occupied about 1,200 acres of the Shinias region on the bay of Marathon, just behind the pine wood along the 3km long sandy seashore. The camp was divided into 11 sub-camps (see Theme of 11) of 1,200 Scouts and Scouters each. The subcamps bore the names of the 10 Athenian clans that fought at Marathon; the eleventh was named after Plateae. There were another 3 subcamps for HQ Staff. About 20 kilometers of roads were constructed at Shinias, for the purpose of the Jamboree.

Campsite facilities included a post office and telephone station, a bank, a fire station, scout shops selling souvenirs, basketball and volleyball courts, a 100-seat hospital, restaurants for the Staff, the Place des Nations with the imposing structure that symbolized the Jamboree's theme, Higher and Wider, a parking area, an 20,000 person amphitheater for opening and closing ceremonies, a photo shop, a barber shop, cinema, religious corners, reunion areas, an arena for national displays, a greek village, canteens in each subcamp and many others.

Aerial photograph of the campsite on May 2017, with the Schinias Olympic Rowing and Canoeing Centre on the left.

| Country (Contigent Leader) | Number of participants | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Aden (J. Fisher) | 2 |

| 2. | Afghanistan | 8 |

| 3. | Algeria | 10 |

| 4. | Armenian Scouts (Dr K. Medzadourian) | 12 |

| 5. | Australia (A.J. Schatzl) | 8 |

| 6. | Austria (Hans Schatzl) | 306 |

| 7. | Barbados (Frank Kay) | 1 |

| 8. | Bechuanaland (Jacob I.B. Sekgwa) | 7 |

| 9. | Belgium (C. Schmit) | 479 |

| 10. | Bermuda (A.J. Swift) | 2 |

| 11. | Brazil (D. Shellard) | 8 |

| 12. | British Guiana (L. Thompson) | 16 |

| 13. | Brunei (Abu Baker Othman) | 10 |

| 14. | Burundi (Joseph Ngendahimana) | 12 |

| 15. | Canada (I.H. Nicholson) | 432 |

| 16. | Central African Republic (M. Edouard Methot) | 1 |

| 17. | Ceylon (E.W. Kannangara) | 16 |

| 18. | China (Formosa) (Lu-Chi-Hwa) | 13 |

| 19. | Congo (Leopoldville) (G. Bwilama) | 10 |

| 20. | Costa Rica (Rico Uffelman Piel) | 1 |

| 21. | Curacao (with Netherlands) | - |

| 22. | Cyprus (Dimitris Dimitriou) | 200 |

| 23. | Cameroons (Aphonse Fauben) | 1 |

| 24. | Dahomey (Samuel Attegbo) | 3 |

| 25. | Denmark incl. Faroe Island (J.B. Skotte Hensen) | 627 |

| 26. | El Salvador (Gilbert Gonzalez Ulloa) | 1 |

| 27. | Faroe Islands (with Denmark) | - |

| 28. | Finland (Ake Romantschuk) | 208 |

| 29. | France (Jean Esteve) | 1202 |

| 30. | Germany (Dr. F. Kronenburg) | 845 |

| 31. | Guatemala (Jose Ruiz Lainfiesta) | 1 |

| 32. | Greece (G. Hasapis) | 1000 |

| 33. | Gilbert & Ellice Islands | 1 |

| 34. | Haiti (K. A. Fisher) | 3 |

| 35. | Hong Kong (Chamson Chau) | 8 |

| 36. | Iceland (Ottar Oktosson) | 28 |

| 37. | India (Jamini Sarkar) | 1 |

| 38. | Iran (Dr. Hossein Banai) | 67 |

| 39 | Iraq | 16 |

| 40. | Ireland (R.G. Tenant) | 60 |

| 41. | Israel (Yehuda Barkai) | 82 |

| 42. | Italy (ASCI: Gino Armeni, CNGFI: Gualtiere Iesurum) | 430 |

| 43. | Ivory Coast (Aka N’Wozan) | 7 |

| 44. | Jamaica (I. E. Jones) | 27 |

| 45. | Japan (Dr. Hidesaburo Kurushima) | 130 |

| 46. | Jordan (Munir Omar Balkar) | 40 |

| 47. | Kenya (H.S. Bahra) | 1 |

| 48. | Kuwait (Thamir I.Sayyar) | 36 |

| 49. | Laos (Chao Singh Saysanom) | 3 |

| 50. | Lebanon (Aboushakra) | 95 |

| 51. | Libya (Teher Tomi) | 11 |

| 52. | Liechtenstein (H.S.H. Prince Emanuel) | 18 |

| 53. | Luxembourg (Jean Welter) | 170 |

| 54. | Malaya (J.A.R. Wellington) | 7 |

| 55. | Malta (John Camenzuli) | 8 |

| 56. | Mexico (R.V. Megana) | 8 |

| 57. | Monaco (Jean Pelacchi) | 16 |

| 58. | Malagasy Republic (Odon Rafenoarisoa) | 11 |

| 59. | Netherlands incl. Curacao (J.C. Versteeg) | 549 |

| 60. | New Zealand (G.A.T. Rhodes) | 33 |

| 61. | Nigeria (G. des Bordes) | 55 |

| 62. | Norway (Odd Hopp) | 145 |

| 63. | Pakistan (M.S. Alain) | 47 |

| 64. | Philippines (Nicasio Fernandez) | 3 |

| 65. | Peru (Teodore Chavez) | 5 |

| 66. | Portugal (Rev.Fr.A.Ferreira Alvez) | 27 |

| 67. | Rhodesia North (E.Barnes) | 17 |

| 68. | Rhodesia South (L.A. Davy) | 31 |

| 69. | Saudi Arabia (A. Sidawy) | 42 |

| 70. | Senegal (Malick Dior) | 10 |

| 71. | Singapore (Bernard Fernandez) | 8 |

| 72. | South Africa (J.D. Draser) | 76 |

| 73. | Spain (Manuel Subira) | 15 |

| 74. | Sudan (Said Mohamed Nur) | 10 |

| 75. | Suriname (Guno Elskamp) | 1 |

| 76. | Sweden (Bengt Ahlstrom) | 424 |

| 77. | Switzerland (Dr. Paul Vork) | 480 |

| 78. | Syria (Manwaffac-El-Shara) | 111 |

| 79. | St. Vincent Island (Gem Hazel) | 1 |

| 80. | Thailand | 8 |

| 81. | Trinidad & Tobago (H.W. Farrell) | 3 |

| 82. | Tunisia (Mahmoud Trigui) | 10 |

| 83. | Turkey (Aziz Ozcelik) | 34 |

| 84. | United Arab Rebublic (H.Ali Abdul Aziz) | 69 |

| 85. | United Kingdom (Air Vice-Marshall B.A. Chacksfield) | 1500 |

| 86. | United States of America (Joseph A. Brunton Jr.) | 650 |

| 87. | Venezuela (Francisco J.Tugues) | 7 |

| 88. | Vietnam | 1 |

| 89. | Zanzibar (Nesser A. Lamki) | 1 |

| Subtotal | 11099 | |

| International HQ Staff | 2618 | |

| GRAND TOTAL | 13717 |

| Sub-Camp | Chief | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Aeantis | J.W.H. Miner, Canada |

| 2. | Aegeis | N. Engberg, Denmark |

| 3. | Akamantis | Dr. G. Reddingius, Holland |

| 4. | Antiochis | J.P.A. Silvester, Philippines |

| 5. | Cecropis | Dr. R. Tremil, Austria |

| 6. | Erechtheis | H.R. Hall, Great Britain |

| 7. | Hippothondis | S. Arthur, Great Britain |

| 8. | Leontis | O. Szymiczek, Hungary |

| 9. | Oineis | E. Bourdet, France |

| 10. | Pandionis | J. W. Fowles, Hungary |

| 11. | Plataea | J. Lioufis, Greece |

| S1. | Hermion (Staff Sub-Camp) | A. Lenos, Greece |

| S2. | Olympus (Staff Sub-Camp) | D. Marcoulis, Greece |

| S3. | Nereids (Women Staff Sub-Camp) | Mrs. P. Skyrianides, Greece |

At Marathon there were "Foreign" Sub-Camp Chiefs, Special Consultants and others on the Jamboree Headquarters Staff as well as in the Sub-Camp Staffs. Speaking generally this experiment was a success, but it did tend to create some difficulties owing to an ignorance of Greek customs and conditions, as well as the language problem.

Perhaps the best example of the workings of the Scout United Nations was in the International Service Troop composed of Rovers and Scouters of many different nationalities, but eventually all working together as one united whole. I would pay a tribute to the Indian Scouter, Jamini Sarkar, who was appointed to head up this Troop. He showed the necessary understanding and diplomacy that must be exercised in any Scout Troop in any country if it is to be a success and be an example of the real Scout spirit.

I believe that some modification of the experiment is called for in the future, but an example has been set and it is to the great credit of the Jamboree Camp Chief, Rann Alexatos, that he not only conceived the idea but carried it through under difficulties. I know something of these as I was privileged to do my best to look after him throughout the Jamboree and to safeguard him from too many questions and interruptions by those who were not so good at accepting responsibility for carrying out their own duties.

But the final conclusion is that the Eleventh Jamboree was in its conduct, its activities and its results truly an INTERNATIONAL JAMBOREE.

The Principle of international staffs, introduced at the Marathon Jamboree was applied most excitingly in the organisation of the Marathon Courier, daily newspaper of the Jamboree. The editor was English, the assistant editors came from France, Greece and New Zealand, the two secretarial assistants were from Egypt and the West Indies and the reporters and correspondents were drawn from contingents of Nigeria, Holland, Greece, Britain, Canada, Cyprus the Scandinavian countries, France, Austria, and Costa Rica by way of Germany.

All had in common either journalistic experience or great interest in the profession - one was foreign editor of a major Dutch newspaper and another a senior reporter on a Nigerian newspaper - and all worked together most magnificently. Though they showed a natural and quite laudable tendency to make sure that their own contingents were not forgotten in the columns of the Courier, there were never any national rivalries.

One of the more curious results of adhering to the international principle was that the staff of the Courier met only at Marathon.

On the Saturday before the Jamboree opened Cecil Henderson of New Zealand, Secretary Jane Wallen from the West Indies, and the writer moved up to Marathon and located the empty tent allotted to the Marathon Courier.

In two days it had been furnished, and then began the long, sometime despairing wait for the staff to arrive. By the Tuesday sufficient had reached the Jamboree for a general conference to be held, but it was two days after the actual opening that the last straggler reported for duty.

One of the longest days the editor ever remembers was that between the expected and actual arrival from Paris of M. Michel Rigal, who had undertaken responsibility for the French pages.

While the newspaper to a certain extent fell together at Marathon, it was not a completely unplanned undertaking. It had, in fact, been most minutely planned during the three months between the decision to produce it and the opening of the Jamboree. That most of the plans had to be changed at the last moment, and improvisations substituted, was perhaps only to be expected.

By the time the last issue appeared, staff members were patting themselves on the back and telling one another that, given another fortnight of trial run, they’d have a nice little paper set up. Unfortunately, time, like the Jamboree, had run out…

The Courier had been planned on what could be described as three levels - the official, the Jamboree, and the sub-camp and contingent.

The official was to have consisted of reports originating from interviews with department chiefs and bulletins from the departments, and interviews with World Committee members and visiting VIPs. This had to be somewhat neglected, partly because the Courier staff was too occupied with Jamboree activities that would not wait, but mostly because department chiefs were overwhelmed by work. World Committee members proved both elusive and, when cornered, uncommunicative, and visiting VIPs never seemed to swim into the Marathon Courier nets.

Jamboree activities were covered in as much detail as possible, and on the whole not too badly, by the volunteer staff of Courier reporters, and sub-camp news, with one or two exceptions, was provided regularly and comprehensively by the sub-camp correspondents - to whom not enough praise has previously been given. For while the reporters were Scouters, the correspondents were all Scouts, on the staffs of the sub-camp chiefs. They brought to their work a freshness and energy that occasional disappointments could not dull and that never flagged beneath the rigours of a climate to which most of them were completely unaccustomed.

On the third level, attempts to persuade troops and patrols to complete the questionnaires prepared for sporting and social activities, and the individual Scouts to enter the Courier easy competition, met with a signal lack of response. But this only proved that, as should have been the case, the Scouts were far too busy, and were enjoying their Jamboree far too much, to devote idle hours to mere clerical labours.

In one sense, the Courier got off to the kind of start that it took several days to recover from. With the experiences of many Scouts in the Skopje earthquake, and the tragic accident to the Philippine contingent, the Courier in its first issue had world, not just Jamboree, news to report. Its editors almost forgot where they were, and had to do some quick rethinking on the second day to get the Courier into its appointed groove.

On this subject, it had been intended to include each day a short section of world news in brief. This was one of several good intentions with which the road to Marathon was paved.

The Courier also was to have been a morning newspaper - which was just another good intention. With a long mountain road between the editorial tent and the printing works, and another four kilometres of busy city streets between the printing works and the actual presses, it was after midday before the day’s papers reached the Jamboree.

With so many kilometres to be covered by manuscript and photographs, bolted plates of type and copies of the Courier, each day’s safe arrival of the newspaper at the Jamboree came to be regarded as a minor miracle.

But that, of course, was not the only miracle worked at Marathon in the summer of 1963.

Pelican (Mr. Courmoulis), Head of the Camp Administration got hold of half a dozen people on July 26. Many elder Scouts also came forward and registered their names. They are now over 300 who are on the job as supplements to the existing units attached to each Sub-Camp.

Jamini Sarkar, the Indian Tea Board’s Welfare Liaison Officer, also a King’s Scout in his country, was the only one to represent the Indian Scouts at the Jamboree. The Indian Tea Board donated 3800 tea caddies for the Jamboree and upon arrival at Marathon, the Organisers of the Jamboree appointed J. Sarkar as the Commandant of the International Emergency Service Troop for handling the various emergency works.

In a gathering like an International Jamboree no man-power should be wasted, hence the creation of the Emergency Service Troop. You will find them doing the work of Police, Reception, Fire Wardens, Water Conservers, Interpreters, etc.

The International team of the E.S.T. is really international; language is no bar, because they speak and can express themselves in the Scout language. To Rann Alexatos, the much-loved Camp Chief, they have pledged to make the Marathon Jamboree a success.

The 370 members of the Emergency Service Troop belonged to the following 24 countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Ceylon, Cyprus, Germany, Greece, India, Italy, Jamaica, Liechtenstein, Lebanon, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan, Singapore, Suriname, Sweden, Switzerland, United Arab Republic, United Kingdom & United States of America.

Emergency Service Troop Group Leaders with the Camp Chief at Marathon

Standing, from left: Raymond Armstrong (Cyprus), Klaus Radicke (Liechtenstein). Eric Lockett (Australia), S. O. A. Ajana (Nigeria), Graeme G’william (Australia), Geoffrey Hughes (U.K.), Andreas Gregoriou (Cyprus), Kevin Donald (Australia), John Heywood (U.K.), Sheila Hiom (U.K.), John Driver (Australia), Keneth Francis (Australia).

Seated, from left: Brian Allan Gray (Australia). Robert Owen (Australia), Col. Martin (U.K.), Genl D. C. Spry, Hony. Jamboree Organising Commissioner & Director, Boy Scouts World Bureau, Rann Alexatos (Camp Chief), Jamini Sarkar (India), Col. J. S. Wilson, Jamboree Special Consultant, Ken Stevens (U.K.) Special Consultant, Jamboree, James Economides (Greece), Miss Molly Stevens (U.K.)

© Copyright 2013, marathon1963.com & proskopos.com. All rights reserved.

No part of the material contained in this website (images, texts, artwork) may be used or reproduced without

written permission or invitation by the publisher. Request permission to use or reproduce material.